|

|

Notes:

Mirrored with permission from www.onecountry.org/e104/e10416as.htm

Crossreferences:

|

10:4

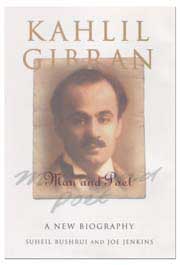

| Kahlil Gibran: Man and Poet Authors: Suheil Bushrui and Joe Jenkins Publisher: Oneworld Publications, Oxford, 1998 Review by: Brad Pokorny  What makes a great artist different from the vast majority of men and

women? How to account for the inspiration and insight that enables someone

like Kahlil Gibran to create one of the century's most popular and enduring

works of literature?

What makes a great artist different from the vast majority of men and

women? How to account for the inspiration and insight that enables someone

like Kahlil Gibran to create one of the century's most popular and enduring

works of literature? Answers to such questions gradually emerge (as much as may be possible, anyway) in an absorbing new biography on Gibran by scholars Suheil Bushrui and Joe Jenkins. Entitled Kahlil Gibran: Man and Poet, the book thoroughly explores the life, loves, times and works of Gibran, whose 1923 book The Prophet has sold more than 10 million copies worldwide and has been translated into at least 20 languages. Born in Lebanon, but a resident of the United States of America for most of his adult life, Kahlil Gibran holds a unique place among modern writers, inasmuch as he wrote well in both English and Arabic and was widely acclaimed in both cultures. Sitting astride two worlds, Gibran created his own unique literary style, one that has won fans in every generation since. "He was one of those rare writers who actually transcend the barrier between East and West, and could justifiably call himself - though a Lebanese and a patriot - a citizen of the world," write Bushrui and Jenkins. "His words went beyond the mere evocation of the mysterious East but endeavored to communicate the necessity of reconciliation between Christianity and Islam, spirituality and materialism, East and West…" In this way, Bushrui and Jenkins establish the theme of the book: that Gibran, for all his personal flaws and foibles, was a genuine artistic visionary whose works are imbued with themes of unity and oneness that are entirely reflective of our century-long march toward global integration and, at the same time, "expressed the deep-felt desire of men and women for a kind of spiritual life that renders the material world meaningful and imbues it with dignity." The story of Gibran's life - apart from his artistic and literary accomplishments - makes for compelling reading. Born in the small Lebanese village of Bisharri in 1883, the son of an alcoholic tax collector, Gibran was brought with his two sisters to America by his mother in 1895 at the age of 12. Although poor and living in a Boston ghetto, his talent for drawing attracted the attention of some of the city's intellectuals, who introduced him to a circle of established artists and writers, including the painter Lilla Cabot and the poet Louise Guiney. At age 15, longing to better understand his heritage, Gibran returned to Lebanon, where he enrolled at the Maronite college of Madrasat-al-Hikmah, then perhaps the foremost Christian secondary school in the Arab world. "This land of mystic beauty became his solace, his source of imagination, and in later years his object of yearning," Bushrui and Jenkins write of Gibran's experiences in Lebanon. After four years, he returned to Boston, to face there in short succession the deaths of one of his sisters, his half-brother and his beloved mother, all of who succumbed to poverty-induced illnesses. Overcoming the impact of these tragedies, Gibran reentered the intellectual and artistic circles of Boston, and he soon found a patron in Mary Elizabeth Haskell, the headmistress of a girls' school who became a financial, intellectual and emotional support to Gibran for much of his life. Until his untimely death in 1931, at the age of 48, from "cirrhosis of the liver and incipient tuberculosis," the rest of Gibran's life was something of a Bohemian whirl. He spent time in Paris and again visited Lebanon but ultimately settled in New York. He never married but, it is clear, had a series of intense love affairs - one of which was carried on wholly by mail. According to Bushrui and Jenkins, he often existed almost wholly on "strong coffee and cigarettes," working long into the night on his writing or artwork. He suffered almost continually from poor health and yet soared upon the spiritual visions of his own inner Muse. Along the way, Gibran met some of the greatest men and women of his time. According to Bushrui and Jenkins, Gibran spent time with the poet William Butler Yeats, the sculptor Auguste Rodin, writer John Galsworthy, and Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung. He also read widely in English and Arabic, and among the writers that touched him greatly were Freidrich Nietzsche and William Blake. Such meetings - whether in person or on paper - refined Gibran's own thinking and direction. When combined with his life experiences, these influences helped shape the singular voice that marked his work, which comprises hundreds of essays, poems, drawings and paintings. Among the important figures who Gibran encountered was 'Abdu'l-Bahá, the son of Bahá'u'lláh, who founded the Bahá'í Faith. In 1912, while visiting New York, 'Abdu'l-Bahá sat for a portrait by Gibran. According to Bushrui and Jenkins, the meetings with 'Abdu'l-Bahá left an "indelible impression" on Gibran, who wrote that in 'Abdu'l-Bahá he had "seen the unseen, and been filled", and that "He is a very great man. He is complete. There are worlds in his soul." Drawing on various sources, Bushrui and Jenkins conclude that 'Abdu'l-Bahá was later to become "the inspiration and template for his unique portrait of Christ" as expressed in his 1926 book, Jesus, the Son of Man, which is widely acknowledged as his second most important work, after The Prophet. They quote Gibran as saying, about 'Abdu'l-Bahá, that "For the first time I saw form a noble enough to be a receptacle for the Holy Spirit." Whether influenced directly by his meetings with 'Abdu'l-Bahá or merely following an inner spiritual vision, it is clear that many of Gibran's views on religion are much in harmony with the Bahá'í teachings. "For Gibran true religion was joyous and liberating: 'teachings that free you and me from bondage and place us unfettered upon the earth, the stepping place of the feet of God'; a God who has given men and women 'spirit wings to soar aloft in the realms of love and freedom' - a religion of justice, which 'makes us all brothers equal before the sun.'" In the end, the portrait Bushrui and Jenkins paint of Gibran is both clear-eyed and loving. By interweaving straightforward facts about his life with incisive quotations from Gibran's own writings and letters, adding in a wealth of observations from those who knew him, and supplying their own perceptive brand of literary criticism, Bushrui and Jenkins have written a tightly woven and yet highly readable narrative that shows how the sum of a man's life - his family background, who he met, what he read, and how he lived - combines every once in a great while to produce someone capable of creating works of literature or art that can move the world. "Gibran became the most successful and famous Arab writer in the world," write Bushrui and Jenkins. "Gibran's message is a healing one and his quest to understand the tensions between spirit and exile anticipated the needs of an age witnessing the spiritual and intellectual impasse of modernity itself." |

| METADATA | |

| Views | 15527 views since posted 1999; last edit 2019-01-06 16:15 UTC; previous at archive.org.../pokorny_bushrui_kahlil_gibran; URLs changed in 2010, see archive.org.../bahai-library.org |

| ISBN | 1018-9300 |

| Language | English |

| Permission | author and publisher |

| Share | Shortlink: bahai-library.com/1056 Citation: ris/1056 |

|

|

|

|

Home

search Author Adv. search Links |

|